Featured Stories

The Liberation of Le Quesnoy

“When they left their farms, small businesses, and professions, and donned their uniforms for King and country to travel to the other side of the world, the men of the New Zealand Division could not have imagined the historic role they would play in the brutalising “war to end all wars”. Nor could they have known that more than 100 years later, some of them would be household names in a small town in France.

Excited by the chance to serve, they were told they’d “be home by Christmas” – but it was not to be.

At Gallipoli, they were shot at, wounded, and the survivors watched friends die. After being evacuated from that hopeless, bloody task in Turkey, they endured another 32 months on the killing fields of the Western Front.

Little wonder that the letters home and diaries of many record their increasing doubts about the seemingly endless war, so far from home.

At this time, New Zealand’s population was about 1million; by the end of WWI more than 100,000 (or 10%) of the country’s population had been involved in the war. Of particular gravity for the new young country was the startling reality that half of all men aged between 18 and 35 left to fight for King and country. This figure was not matched by any other allied country, and for the next 30 years this would profoundly affect New Zealand in terms of society, business and leadership. It would happen again only 25 years later…..”

NZ Soldiers in Germany 1918

“Under the conditions of the Armistice signed on 11 November 1918, Germany had 14 days to evacuate from all remaining occupied territory – as well as from German territory claimed by France and Belgium. The Allies quickly sent their armies to occupy the Rhineland and ensure that Germany would not break the ceasefire.

Most of the New Zealand Division were billeted at Beauvois and Fontaine when they heard news of the armistice. On 28 November, they began a 240-kilometre march towards trains that would then take them to the German town of Cologne. There, they would become part of the Allied occupation force, ensuring there were no uprisings.

The Māori Pioneer Battalion also marched to the border near Cologne, but at the last minute, the British authorities decided they should not be part of the occupation force, and sent them home. Amongst the men of the Māori Battalion there was a mixture of resentment and relief.

Some of the soldiers who did occupy Cologne described the experience of arriving there. Private Neil Ingram wrote, ‘As we marched through the city of Cologne I was struck with the fine appearance of the place. Great wide streets, beautiful avenues of trees and fine big buildings of elaborate architecture. I often wondered, during our march, how the Germans would receive us when we eventually appeared marching through their streets, led by playing bands. Well! Strangely, I thought, they seemed to completely ignore us. Some glanced gravely or casually at our marching khaki column and others simply didn’t glance at all.”

Photo of New Zealand troops marching over the Hohenzollern Bridge, Cologne, 1919.

Image courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref 1/1-002127-G.

Royal New Zealand Returned and Services’ Association: New Zealand official negatives, World War 1914-1918.

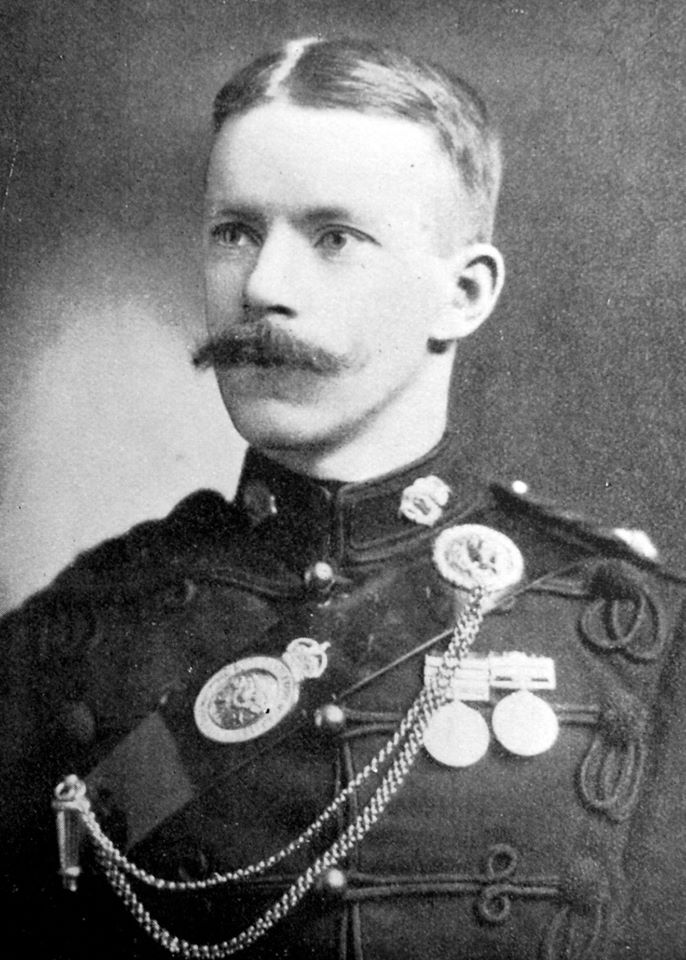

Major Percy John Overton

Percy Overton in the full dress uniform of an officer in the Amuri Mounted Rifles in about 1909.

Credit: Christ’s College Register.

Major Percy John Overton

“The second-in-command of the Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiment was Major Percy John Overton, No.7/384, a 38-year-old Canterbury sheep farmer. He left a wife and four young children in New Zealand.

Overton had served in the South African War distinguishing himself as a scout. In April 1902 he was mentioned in dispatches for his outstanding work.

On Gallipoli he put his scouting expertise to good use. Overton led a group of scouts who explored the extremely rough, but lightly held ground to the north of Anzac Cove. This area, which led up to the Sari Bair range, was the only place in which it might be possible for the Australians and New Zealanders to break out and outflank the Ottoman forces besieging them. Remarkably Percy Overton wrote freely about his sensitive work in letters he sent home and which were subsequently published in the Christchurch Press.

In one letter written at the end of May he wrote:

I do not get much sleep at night, but make this up during the day when things are quiet. I have been doing some reconnoitring for General Birdwood outside our outposts and through the Turkish lines, which is most interesting work. The first time I took Corporal Denton, and we had a great day together, and gained a lot of valuable information. The last time I was out for two nights and a day with Lieutenant McInnis and Corporal Young. We had a most exciting and interesting time dodging Turkish outposts, and I would not have missed the experience for anything. I was able from what I saw of the country to make a useful map and find out the movements of the Turks.

During his scouting missions in Overton showed remarkable coolness and daring. During the mission with McInnis and Young he found what appeared to him to be a practical route leading up to Hill Q North of Chunuk Bair. The intelligence gathered by Overton played a crucial part in the planning for the Allied offensive of August 1915. In the offensive, which began on the night of 6/7 August, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade and Maori Contingent had to clear the rugged and complex ground in front of the Sari Bair range so that the Allied assault columns could attack Chunuk Bair, Hill Q and Hill 971 (Koja Cheman Tepe).

Major Percy Overton was killed on 7 August 1915 while guiding troops of the 29th Indian Brigade towards their objective, Hill Q. He was, it appears, killed before he realised that he may well have sent the Indians along an incorrect route. At the time of his death he was described by one brother officers as the “most brilliant and fearless of us all” who was as usual showing scant regard for his personal safety.

The history of the Canterbury Mounted Rifles, after noting that the Regiment suffered 40 percent casualties in the fighting during the opening of the August defence, commented that: Among all the gallant fellows who died during the bitter August fighting none was missed more than Major Overton. He was one of those rare men to whom the best was not enough. Ever on the look out to do more, to improve the set task, to alleviate the conditions under which the Regiment laboured, he was an inspiration to all.

Major Percy Overton was posthumously mentioned in dispatches.